Larry Harris is raising money to install a historical marker in front of this building, the original Friendship School where African American students attended class until the 1950s. “The school was more than the school,” he says. “The first movie I ever saw was in that school, and it stays with me today just like it was yesterday.”

Larry Harris’ family has lived in Wake County for more than a century — since freedmen, newly emancipated slaves, Native Americans and white farmers agreed to live in peace and to call their community Friendship.

Today, most Apex residents associate Friendship only with the high school on Humie Olive Road.

But within sight of Apex Friendship High School stands the original 1924 Friendship School, and Harris wants to make sure it — and the community he grew up in — aren’t forgotten.

“A lot of people have been lost from the Friendship community,” he said. “That’s why it’s so important for us to get the history, and get it quick, because people are dying.”

Harris is leading efforts to install historical markers at the sites of three school houses — all built with the help of philanthropist Julius Rosenwald in order to educate African American children in the Jim Crow era.

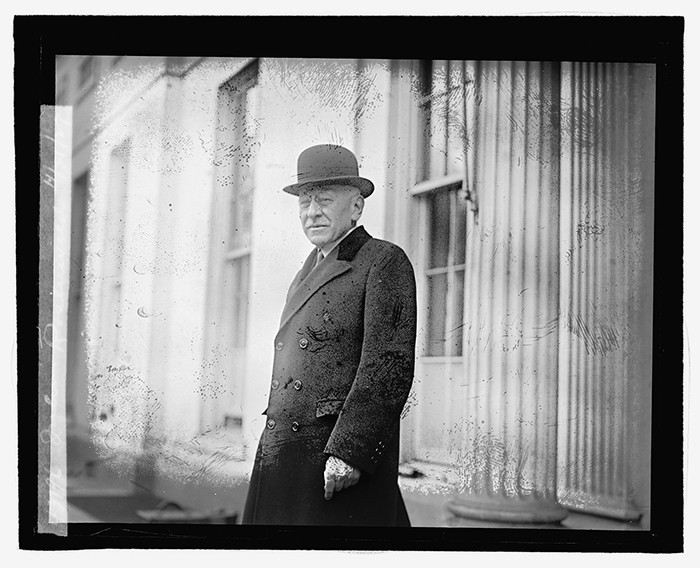

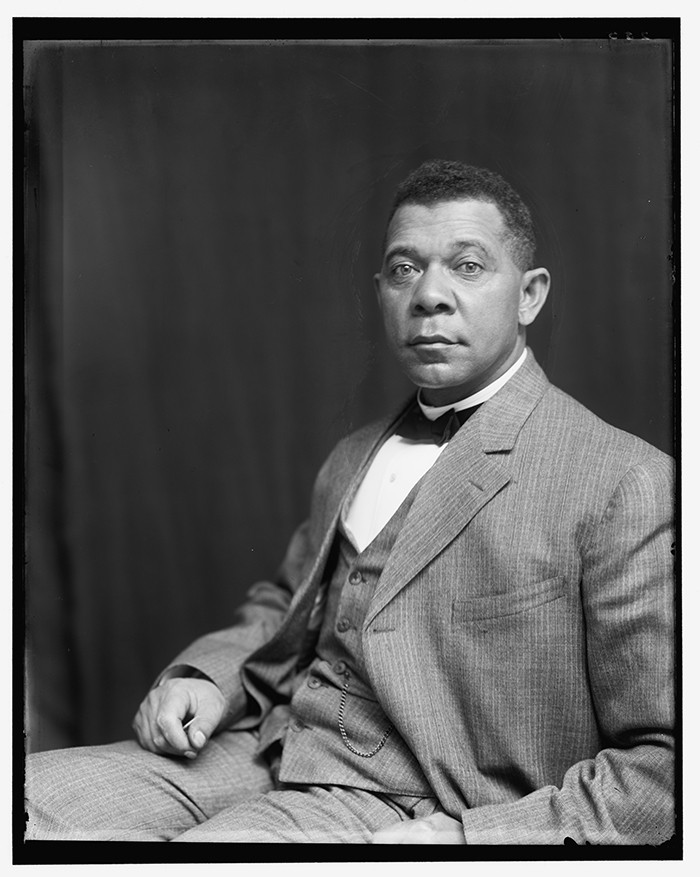

Julius Rosenwald, president of Sears, Roebuck and Co., became concerned about the inadequate education most African American children were receiving, especially those living in the rural South. After meeting Booker T. Washington, below, Rosenwald established a fund to provide matching grants for communities to build schools. Roughly 5,300 schools were built in the effort, called the most important initiative to advance black education in the early 20th century. Library of Congress, 1929

“When the Rosenwald schools opened, it was just a whole other world for us to see,” said Harris. “This was a way for us to lift ourselves out of poverty.”

In January, the Apex Town Council agreed to help pay for a historical marker at the Friendship School and at sites in Apex and New Hill. The town will contribute up to $2,000 in a 50-50 match. Harris hopes to raise around $4,000 to pay for the first marker.

The Rosenwald Fund

To understand the importance of the Rosenwald schools, it helps to take a historical view, says Earl Ijames, a curator at the N.C. Museum of History.

Booker T. Washington. Library of Congress.

In 1868, the North Carolina constitution was amended to guarantee a free public education for everyone aged 6 to 21, no matter their race. But 30 years later, after the “separate but equal” Supreme Court decision and the enactment of Jim Crow laws, that lofty goal was no more.

“In 1901, we have a society that essentially has broken down any type of expectation of having an integral education with all children,” said Ijames. “If there’s any education for people of color at all, it’s very marginal.”

In 1912, Rosenwald, the president of Sears, Roebuck and Co., met Booker T. Washington and was inspired by the black educator’s work at Tuskegee University in Alabama. The Chicago businessman established the Rosenwald Fund, which was to address the chronic underfunding of segregated schools.

Operating on a public-private model, the fund required grass-roots investment. Although the specific percentages varied by school, most black communities had to come up with 40% of a school’s cost. The Rosenwald Fund would ante up another 40%, and the local government would be responsible for the remaining 20%, says Ijames.

“That worked to help uplift a literal whole generation of people who were being subject to the abject horrors of Jim Crow,” said Ijames. “It allowed and afforded two or three generations of people to get a quality education, even in the midst of separate and unequal.”

From 1913-1932, some 5,300 schools were built in 15 southern states, and with more than 800, North Carolina had the most. In Wake County alone, 27 Rosenwald schools were built.

The Friendship School

The Friendship School, built in 1924, featured a two-classroom floor plan, likely built from architectural plans provided by the Rosenwald Fund. The schools often had no electricity, so most had tall double-sashed windows to catch the natural light. Fisk University, John Hope and Aurelia E. Franklin Library, Special Collections, Photograph Archives

“It was a time of great excitement and community spirit, because the people claimed the school for themselves,” Harris said of the Friendship School. “People took pride in education.”

The two-teacher school cost $2,790, with the community donating $890 and the Rosenwald Fund adding $700. Besides raising the initial capital, local families also provided labor to build the school.

Harris, whose family farm stretched 60 acres from Mount Zion Baptist Church north to Beaver Creek, grew up nearby.

Although he never attended as a student, Harris has fond memories of the school. As a boy, he had a playmate who was several months older, and when his friend went off to first grade, Harris was left at home. Despondent, he asked his mother: Why couldn’t he go to school too?

“I think she felt bad about it, so she volunteered to go help Miss Spence. She was the one teacher at the Friendship School,” he said. “My mother took me as if to say, ‘Well, okay. You’ll be going to school anyway.’”

The Friendship School is one of the few Rosenwald schools still standing in Wake County. Of the 5,357 schools, shops and teacher homes constructed between 1917 and 1932, according to the National Trust for Historic Places, only 10-12% are estimated to survive today.

By the time he was ready for school the next year, he told his mother he didn’t want to go.

“I was so excited about the Rosenwald school, I didn’t want to leave it. I wanted to go to school there, because my mom was a teacher,” he said.

Last year, Wake County Schools launched “Respecting Our History, Building Our Future,” a project to document the history of local segregated schools while alumni and teachers are still able to share their experiences. wcpss.net/domain/16337

The Friendship School was closed in the 1950s, sold and remodeled into a private home. The nondescript structure now stands empty.

Although the New Hill School building is gone, Harris would like to remember the school with a marker at what is now the corner of New Hill Holleman and Church roads. The 1923 three-teacher Rosenwald school also closed in the 1950s and, according to Harris, it became a dance club where African American teens could listen to music and socialize.

As rural schools like Friendship and New Hill closed, black children were sent to Apex, to attend another school made possible by Rosenwald money.

The Apex School

The Apex School, completed in 1932, was a six-teacher school with a classroom, an auditorium, a library and an office. The brick structure on Tingen Road cost $11,200 to build, with the African American community contributing $1,500, the Rosenwald Fund paying $2,000 and the county picking up the rest.

The Apex School, built in 1932, was one of the few bricked Rosenwald schools. During the mid-forties, the school became Apex Junior High with grades 1 through 9. It became Apex Consolidated High School in the ’50s, when 11th and 12th grades were added. In 1992, the structure was torn down to make way for the current Apex Elementary School.

Prominent local minister Rev. James Hayes Baldwin and his wife, Mary Margaret Crutchfield Baldwin, donated the land for the school. Their granddaughter Helen Stewart Davenport attended the Apex School from first grade through high school, graduating in 1959.

She describes the school, which was called Apex Consolidated High School when she attended, as better than some of the one-room schools in the community like Friendship and New Hill, but it didn’t compare to the white schools.

“You have to recall now this is Jim Crow days,” she said. “Supplies were scarce; opportunities were scarcer. You just had one way to go. The opportunities weren’t there. You would either have to preach or teach. If you became a lawyer, you had to work in the black community.”

Wake County Public Schools

Although opportunities were limited, many graduates went on to attend college at Shaw University, St. Augustine’s or one of the other historically black colleges or universities. Davenport, herself, graduated from N.C. Central University in Durham.

These college-educated men and women returned to the community, and landed jobs that led to middle class lives and impressive new cars, says Harris, who graduated from Apex Consolidated in 1963 and Norfolk State University in 1968.

“It was the spark that set the fire for education within our black youth, and by the time we were ready to go off to college and get out of high school, we were inspired,” he said.

Courtesy of the State Archives of North Carolina, Raleigh, July 1989

Lasting impact

If you’d like more information about the efforts to install historical markers at Apex’s Rosenwald schools, email Larry Harris at dobbieh2008@hotmail.com.

In the early `70s, the Wake County schools desegregated, and the Apex School became, first, a middle school and eventually, an elementary school. The old structure was razed in 1992 to make way for the current Apex Elementary School.

Although these African American schools are gone, it is important to remember their importance then and now. Ijames draws a direct line from the Rosenwald schools, through the flourishing of the HBCUs in North Carolina, to the current high level of post-secondary education in the Triangle.

“We have a highly educated class of people that you don’t find on par anywhere else in the South,” he said. “And part of the reason why that is, is because of the Friendship Rosenwald School and the other 812 Rosenwald schools that dotted throughout North Carolina.”

- Art of Aging Gracefully

- In the Mix

- A Pocket Full of Parks

- In Healing Color

- Small Business Spotlight: Rush Cycle

- Nonprofit Spotlight: Alliance Medical Ministry

- Remembering Rosenwald

- From the Editor: April 2020

- Green Scene

- Liquid Assets: No’Lasses from Fair Game Beverage Co.

- Liquid Assets: Vitruvius IPA from Craftboro Brewing Depot

- Garden Adventurer: Fringe Gardening