At True ABAlities Preparatory School, success is defined differently. For Founder & Executive Director Lauren (Brennan) Womble and her teaching team, it’s the 11-yearold child who — for the first time — blows out the candles on their birthday cake.

Working for two decades with neurodivergent children has taught Womble that learning environments are failing to ask: “What are we trying to get to?”

After being introduced to a program based on a functional application of Applied Behavioral Analysis designed to apply to students with various needs, Womble discovered that “When services are set up to serve learners in a way that result in long-term adult outcomes, it’s night and day what you see.”

So, when she returned to North Carolina and found nothing similar in existence, Womble “wanted to create it.”

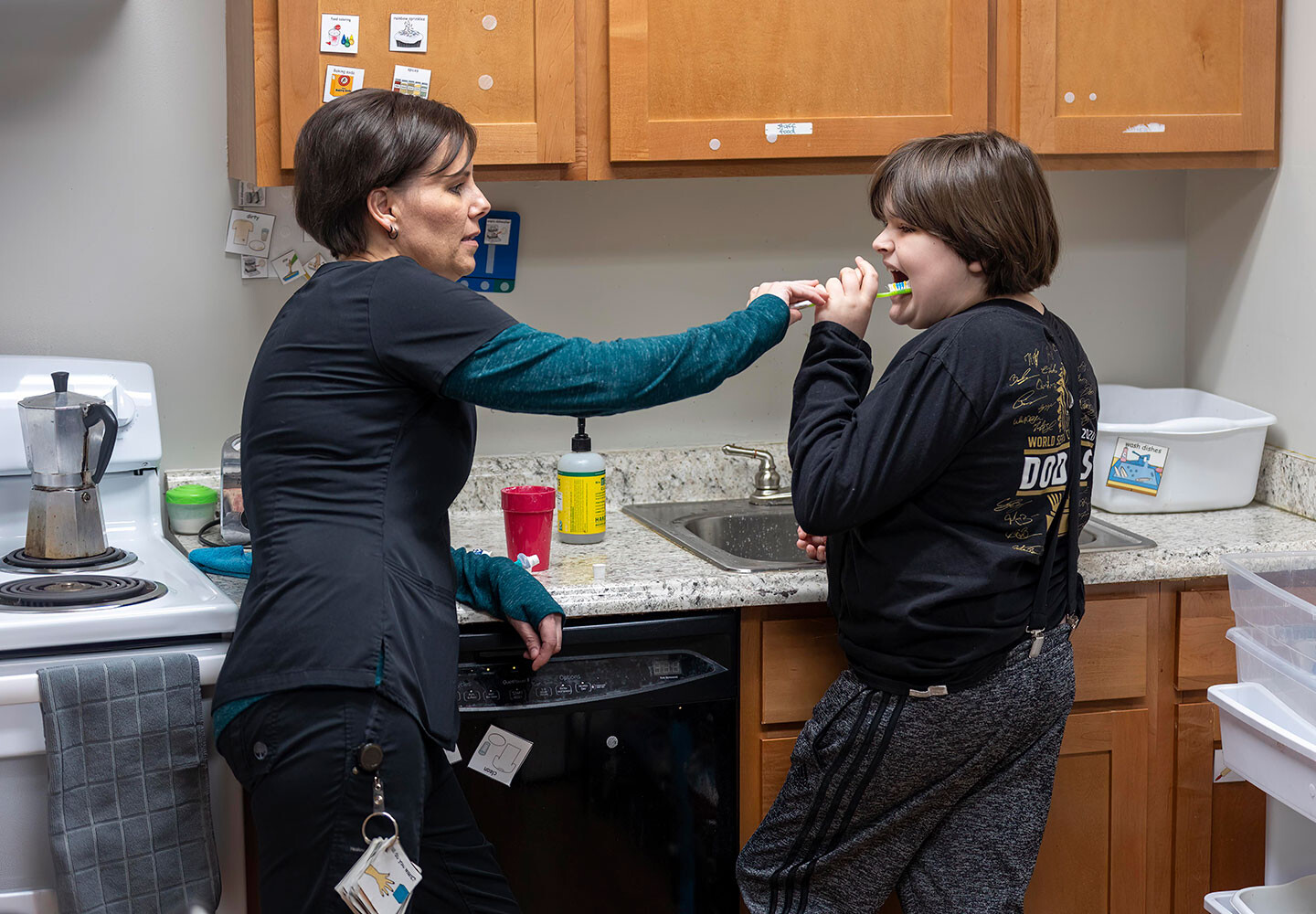

Visual aids assist with teaching functional communication.

And create it she did.

Relying on the Pyramid Education Approach, which, as Womble said, “roots us all,” TAPS teachers use a teaching strategy that breaks complex topics into smaller and more manageable parts for their neurodiverse learners between the ages of 4 and 18.

The Cary private school is Womble’s answer to the critical yet unasked question. As she explained: “The goal is for these learners to develop into adults who are happy and healthy and able to live a well-rounded life — and that’s all neurodiverse individuals, regardless of impact of their neurodiversity.”

When it comes to the long-term outlook for TAPS learners, “We want them in jobs,” Womble said. “We want them to live as independently as possible. We want them to have a community that they’re a part of. We want them to have hobbies. We want them to have health and wellness, exercise, knowing how to eat well. We want them to have everything that all of us want for ourselves.”

For TAPS’ 21 current learners, placement is based not on age but on level of language. “We look through the lens of language” when it comes to placing and serving students, Womble explained, as “language drives everything.”

As such, the school comprises four different programs and two tracks, with the social-emotional track suited for fully developmentally appropriate learners with their language who require support with high-level social skills and emotional regulation.

The second track is functional communication, which occurs in 4–8 and 12–18-yearold classrooms and serves learners who are non-vocal or may have a communication system that isn’t being used in a functional way to convey their basic wants and needs.

“A hundred percent of the time,” Womble asserted, learners and their families come to TAPS frustrated and fearful.” Parents have often gone to multiple places and trusted multiple people with their learner, only to end up distraught when things don’t go well. “It’s a trauma,” Womble said. “And their children are getting traumatized.”

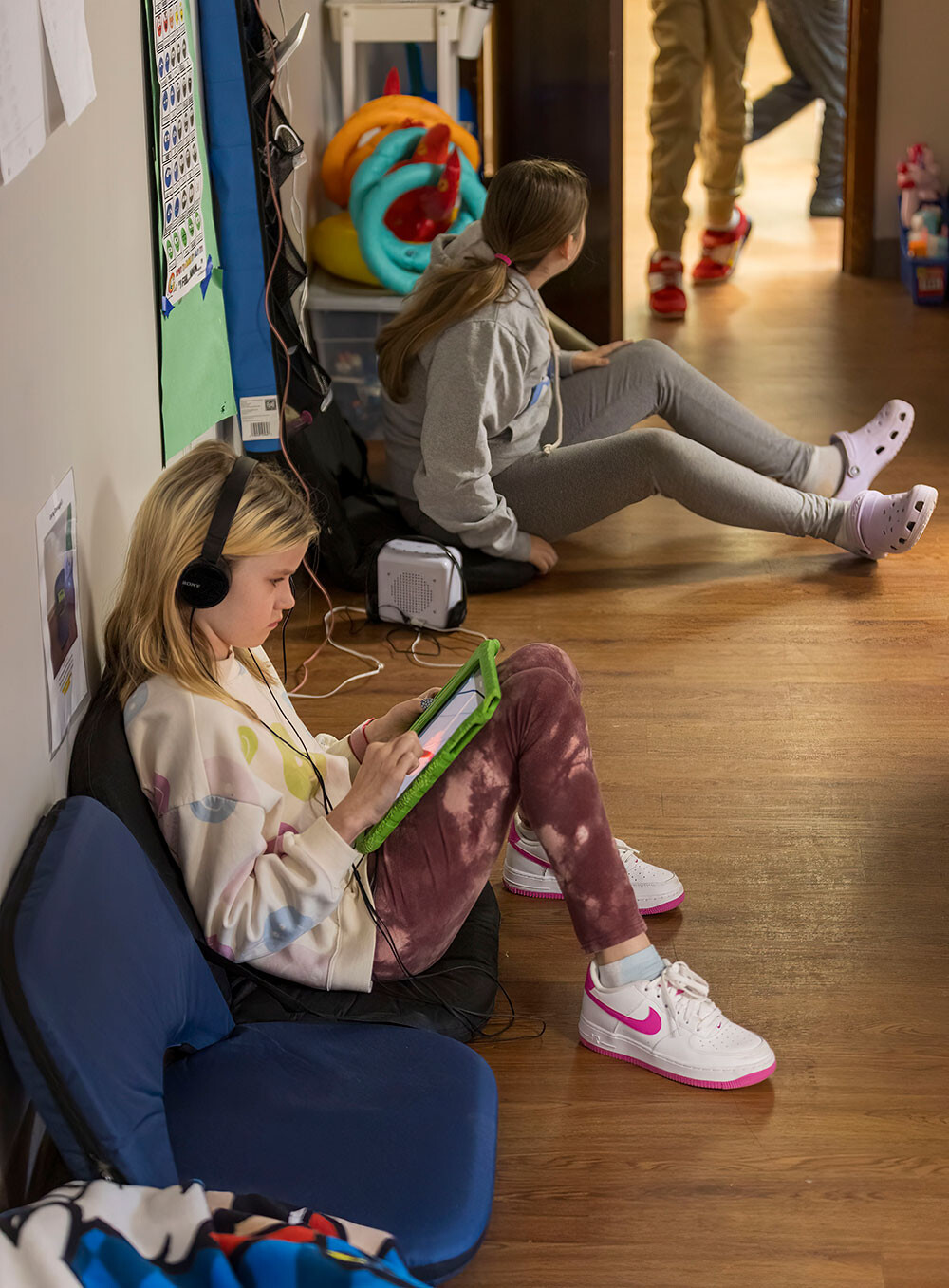

Learners take time for themselves in the hallway before heading to class.

Indeed, from disliking school to distrusting teachers, TAPS teachers find that much of their initial attention is focused on repairing the student-teacher relationship and helping learners feel safe in their educational setting.

“It breaks my heart to tell parents there’s a wait list,” Womble said. “We have so many families waiting for us to open that next room” — which would fill the current unserved 9–12-year-old group.

About TAPS’ word-of-mouth recognition, Womble shared: “There’s not a truer measure of whether we’re doing what we set out to do than what people are saying in the community about us.” After all, “We’re not here for the successes that we see in our classrooms every day,” Womble said. “We’re here for the successes that happen at home because that’s where it matters: out in the community.”

“We want to broaden a child’s life,” Womble explained about TAPS’ long-term approach. Often, for families with neurodiverse children, their world has become quite small. “Everything we do is to expand and open that world back up.”

For the TAPS teachers doing so, “It has to be a calling,” Womble said. “This feeds their soul. This is purpose for them.” With TAPS teachers using their own vehicles to transport learners out into the community every week, an activity integral to learners’ adult outcomes, Womble shared: “It would be amazing to have some sort of transportation for the kiddos.”

Expanding the school’s scope in the community will require funding — people feeling what Womble described as a “tugging on their heart” that compels them to act. Having outgrown their building, TAPS’ 9–12-year-old room — along with a “laundry list of services” she’s eager to unveil — is on hold.

Much like the child still waiting to blow out their birthday candles.

- 2024 Maggy Awards: Shopping

- 2024 Maggy Awards: Services

- 2024 Maggy Awards: Lifestyle

- 2024 Maggy Awards: Restaurants

- The 2024 Maggy Awards: Western Wake’s Most Wanted

- Garden Adventurer: The Edible Oddity: Patty Pan Squash

- Liquid Assets: Kiwis Fly North

- Liquid Assets: Reifenberg

- Restaurant Profile: SAAP Laotian Restaurant

- Nonprofit Spotlight: True ABAlities Preparatory School (TAPS)

- Boomtown: Apex Turns 150

- Erica Chats: Feeling Stuck?

- On Trend: Modern Caricatures

- Small Business Spotlight: Cary Dance Productions

- Pursuing Greatness

- Things to Do: April 2024