For anyone who’s ever felt excluded, inadequate or thwarted in life … meet Dr. Lucy Daniels.

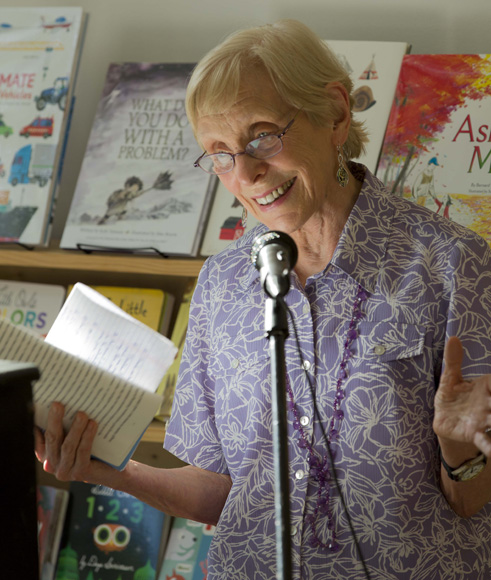

Tiny in stature but larger than life in her against-the-odds accomplishments, spend an hour with Daniels and you’ll come away inspired, and more than a little awed.

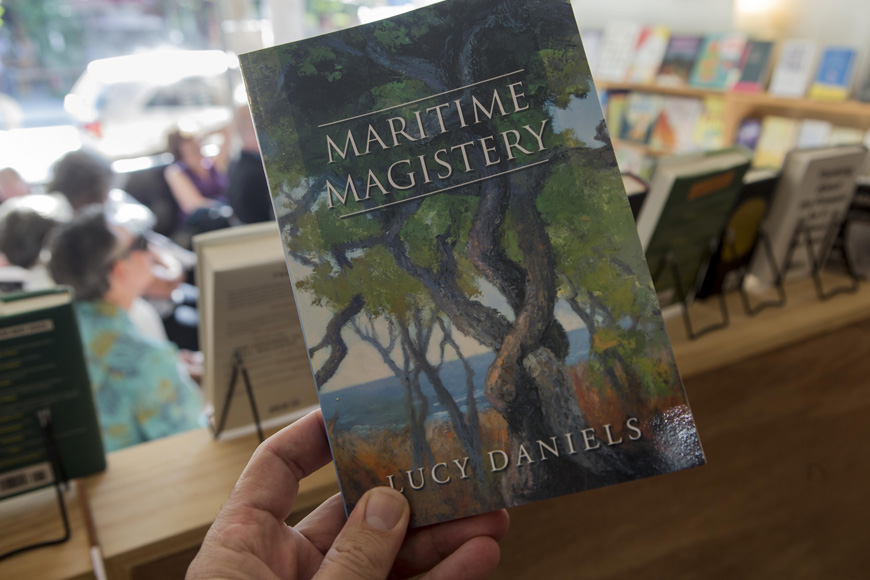

Daniels last appeared on the pages of Cary Magazine as a Women of Western Wake honoree in 2008. Now at age 82, she’s the subject of a documentary titled “In So Many Words,” and recently released her sixth book, “Maritime Magistery.”

Ask her about these successes, and she smiles enigmatically.

“I don’t know that success matters so much as being alive,” Daniels said, “feeling vital, being invested, and working on what really matters.”

The backstory

To truly understand that statement, you have to know her backstory: Born into Raleigh’s high society as a newspaper heiress, Daniels grew up materially rich yet emotionally deprived.

As a teen, she developed severe anorexia and spent five years in a psychiatric hospital where she endured electroshock treatments without anesthesia.

Here’s the awe-inspiring part: From her hospital room, Daniels wrote the national bestseller “Caleb, My Son,” becoming the youngest-ever recipient of the Guggenheim Fellowship in literature at age 22, despite being a high school dropout.

She followed that with a required second novel, “High On a Hill,” a fictional account of her years in confinement.

To address the dichotomies of her life, Daniels tells a story.

“As a child I had crossed eyes and needed surgery. I looked weird, and they kept me in the yard by myself. I knew nobody would look for me if I got lost, so I learned that I needed to take care of myself,” she said.

“In truth, that’s what we all have to do. You can call it wisdom, or the capacity to use life.”

This outlook is hard-earned for Daniels. Following the success of her first two books, she continued to battle anorexia and a decades-long writer’s block, while rearing her four children.

Daniels pushed her way through college and psychoanalysis, in a quest for emotional and creative freedom.

“For me, creative freedom is knowing what stopped me from doing the work, what makes me free to have different ideas, and gives me the ability to let people read and criticize my work,” she said. “Our experiences don’t go away, but we can learn to deal with them better. That helps us grow.”

She earned a doctorate in clinical psychology and maintains her private practice today, where she helps others find their own paths to freedom, often through analysis of their dreams.

In 2014, Daniels was honored with the first-ever Lifetime Achievement Award given by The International Symposium on Psychoanalysis and Art.

At home, her remarkable life includes eight grandchildren and a dachshund named Maggie.

No more secrets

Letting go of long-held secrets was part of Daniels’ recovery. She hadn’t told her early story even to her children, until one of them came home from school seeking answers to rumors about her.

Her response was to reclaim her maiden name of Lucy Daniels, and begin sharing her story.

“I did it because of what had happened to me,” she said. “It’s good not to have secrets.”

Daniels sold her share of the family business and in 1989 established the nonprofit Lucy Daniels Foundation and The Lucy Daniels Center for Early Childhood.

The foundation helps creative people achieve their own emotional freedom through psychoanalytic education. She has led the seminar Our Problems as the Roots of Our Power annually since 1992.

“Creative people have a way of mastering psychic trauma through their creative work,” Daniels said. “They take the bad things that happen to them and actively reshape those painful experiences into something else, a book, or a painting, or a composition.

“We learn that our problems can be used to our advantage,” she said. “Dreams can show you why you have problems in your work, and then you can deal with them rather than let them cripple you.”

The foundation’s unique eight-year study of creative writers undergoing psychoanalysis has produced data that’s used by researchers internationally.

Meanwhile, the Center for Early Childhood provides comprehensive mental health services for children, paired with academic programs through its elementary school.

In 2002, Daniels finally broke through her long-term writer’s block with the release of her memoir, “With a Woman’s Voice: A Writer’s Struggle for Emotional Freedom.”

And in 2005, she published “Dreaming Your Way to Creative Freedom,” and her first novel in more than 40 years, “The Eyes of the Father,” a story of people controlled by the past.

Her collection of stories “Walking with Moonshine” came in 2013, as did a documentary by filmmaker Elisabeth Haviland James. The film explores the childhood that has both tormented and motivated Daniels, the dynamics of anorexia, and her growth through psychoanalytic treatment.

Daniels’ latest book is a collection of short stories set at the North Carolina coast, paralleling the transformation of the land due to environmental and commercial factors to life’s human evolutions.

She says the book won’t be her last.

“I know I have to write,” Daniels said. “My next project is on aging, the good and the bad about the process. You may lose abilities as you age, but not necessarily thinking or feeling. What becomes important is how to use the changes, and not be stopped by them.

“It’s wonderful to have a companion like writing,” she said. “As you age, the more things you know to write about, because you have increased your experience. And I’m a better therapist than I was 10 years ago.

“My priorities now are my practice, my writing, and my friends and family. Writing and clinical work benefit my life and make it more satisfying at this stage.”

For all of the contradictions of Daniels’ life, she says she’s been fortunate.

“More people have been through bad times than we know,” she said. “I’ve found a lot of luck in being resilient.”